Why discuss Adversarial Robustness?

Machine learning models have been shown to be vulnerable to adversarial attacks, which consist of perturbations added to inputs designed to fool the model that are often imperceptible to humans. In this document, we highlight the several methods of generating adversarial examples and methods of evaluating adversarial robustness.

History of Adversarial Attacks

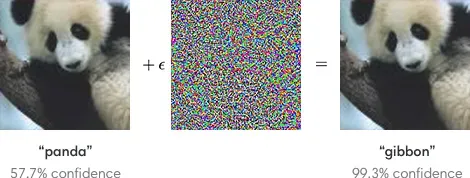

Adversarial examples are inputs to machine learning models designed to intentionally fool them or to cause mispredictions. The canonical example is the one from Ian Goodfellow’s paper below.

(Source: OpenAI "Attacking Machine Learning with Adversarial Examples")

While adversarial machine learning is still a very young field (less than 10 years old), there’s been an explosion of papers and work around attacking such models and finding their vulnerabilities, turning into a veritable arms race between defenders and attackers. Attackers essentially have the upper hand because breaking things is easier than fixing them. A great analogy to adversarial ML is cryptography in the 50s: researchers kept trying convoluted ways of securing systems, and researchers kept trying to break them, till they invented a convoluted algorithm that was probably too computationally expensive to break (DES).

To that end, let us try to define what an adversarial sample on a model looks like. Mathematically, let us assume that we have a model f with an input x that can produce a prediction y. Then, an adversarial example δ for the model f and input x can be defined such that:

- f(x+δ) != y, implying that the perturbation δ added to x does not produce the same prediction as x

- L(δ) < T, where L is some generic function that measures the norm of δ, and where T is some upper bound on this norm.

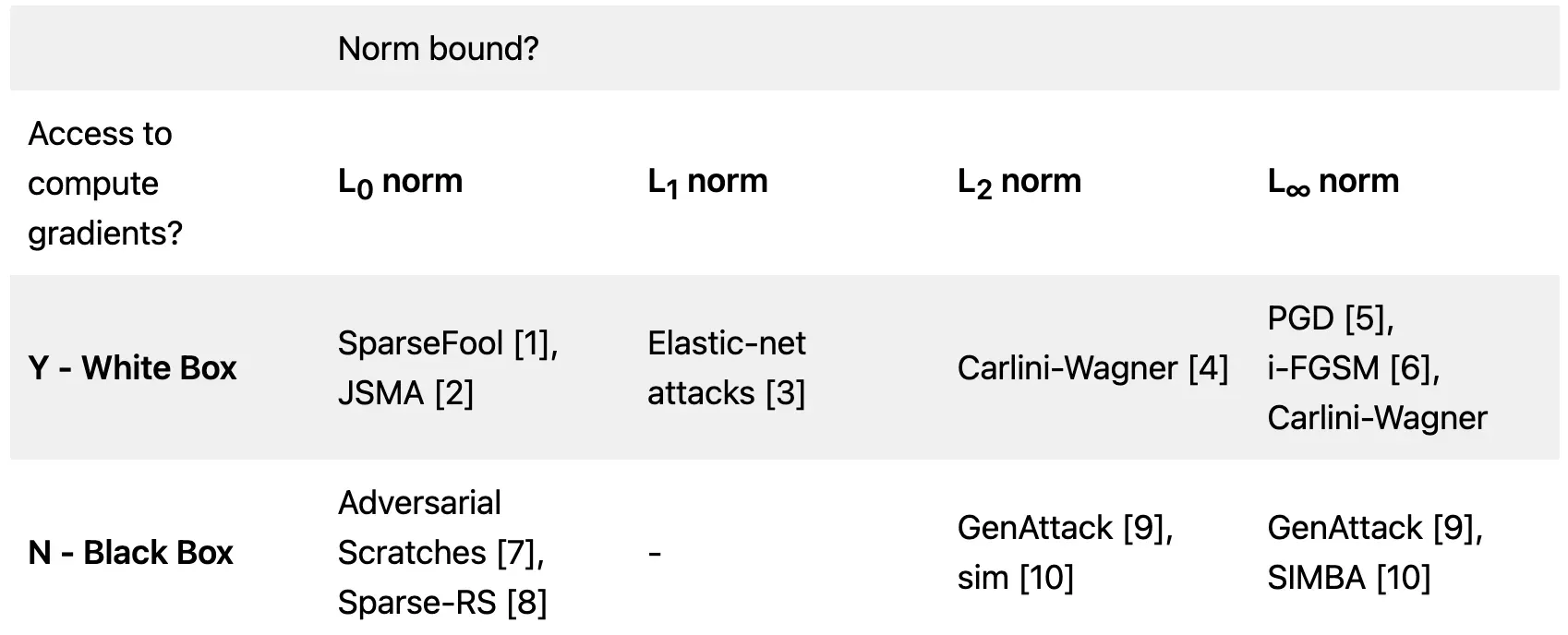

Based on the above parameters, there is a large family of algorithms that can be used to generate such perturbations. Broadly, they can be split up as follows:

At a very high level we can model the threat of adversaries as follows:

Gradient access: Gradient access controls who has access to the model f and who doesn’t.

- White box: adversaries typically have full access to the model parameters, architecture, training routine and training hyperparameters, and are often the most powerful attacks used in literature. White box attacks use gradient information to find adversarial examples often.

- Black box: adversaries have little to no access to the model parameters, and the model is abstracted away as an API of some sort. Black box attacks can be launched using non-gradient based optimization methods, such as (1) genetic algorithms, (2) random search, and (3) evolution strategies. They are usually not very efficient in terms of computational resources but are the most realistic adversary class.

Perturbation bound: Perturbation bound determines the size of the perturbation δ, and is usually measured with some mathematical norm such as the Lp norm.

- L0 norm: An L0 norm bounded attack typically involves modifying a certain number of features of an input signal to a model. L0-norm bounded attacks are often very realistic and can be launched on real-world systems. A common example is a sticker added to a stop-sign that can force a self-driving car to not slow down - all the background is preserved, and only a tiny fraction of the environment is modified.

- L1 norm: An L1 norm bounded attack involves upper bounding the sum of the total perturbation values. This attack is quite uncommon.

- L2 norm: An L2 norm bounded attack involves upper bounding the Euclidean distance/Pythagorean distance of the perturbation δ. L2 norm bounded attacks are used quite commonly due to the mathematical relevance of L2 norms in linear algebra and geometry.

- L∞ norm: An L∞ norm bounded attack involves upper bounding the maximum value of the perturbation δ, and was the first attack to be discovered. Linfinity attacks are studied the most out of all because of their simplicity and mathematical convenience in robust optimization.

At a very high-level, we can have 8 different kinds of attacks (2 x 4) highlighted below if we use the Lp norm as a robustness metric. There are several other domain-specific ways to quantify the magnitude of the perturbation δ, but the above can be generalized across all input types. Note that the attacks cited below are strictly for images, but the general principles can be applied to any model f.

Conclusion:

As machine learning models become increasingly embedded in products and services all around us, their security vulnerabilities and threats become ever more important, and monitoring becomes even more critical. We’ve highlighted different methods an adversary might launch an adversarial attach against a pre-trained model, but as we find more examples, we will make sure to write another post and share the findings. In the meantime, check out our other data science blogs.

—

Sources:

[1] Modas et al., SparseFool: A Few Pixels Make a Big Difference, CVPR 2019

[2] Papernot et al., Practical Black-Box Attacks against Machine Learning, ASIA CCS 2017

[3] Sharma et al., EAD: Elastic-Net Attacks to Deep Neural Networks. AAAI-2018

[4] Carlini et al., Towards Evaluating the Robustness of Neural Networks, IEEE Security & Privacy, 2017

[5] Madry et al., Towards Deep Learning Models Resistant to Adversarial Attacks, ICLR 2018

[6] Goodfellow et al., Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial Examples, ICLR 2015

[7] Jere et al., Scratch that! An Evolution-based Adversarial Attack against Neural Networks, arxiv preprint: https://arxiv.org/abs/1912.02316

[8] Croce et al., Sparse-RS: a versatile framework for query-efficient sparse black-box adversarial attacks, ECCV'20 Workshop on Adversarial Robustness in the Real World

[9] Alzantot et al., GenAttack: Practical Black-box Attacks with Gradient-Free Optimization, GECCO '19

[10] Guo et al., Simple Black-box Adversarial Attacks, ICML 2019